Bund in 1930s

The Winner of “Sharon Matsumoto and Ron Rose Award” at History Day In California State Finals

by Yiren Lu

10th grade, Maria Carrillo High School, Santa Rosa, California

For over 20,000 European Jews in the late 1930’s and early 1940’s, Shanghai was once home. It meant desperate conditions, constant hunger, and strange languages. It meant traversing thousands of miles of uncertain ocean to reach a crime-infested, chaos-accustomed city. But most importantly, Shanghai meant a safe haven from Hitler and the Holocaust at a time when the Nazi flag flew from Paris to the Baltic.

The story of the great escape of Jews to Shanghai has been a tragedy and a triumph almost seventy years in the making. The starry eyed teenagers that arrived on the docks of the Bund in 1939 are themselves grandparents now. Time has dulled the hard edge of cruel memories, and “recollections have become episodic and selective… nostalgic and romantic, increasingly shrouded by the mist of a long ago past” (Falbaum 13). Yet “romantic” or “warm” intentions could not have been farther from the truth. Shanghai was their destination only because there was no other option.

Introduction

By the late 1920’s, Shanghai was already China’s commercial hub, a young city named literally “on the sea”, and home to a thriving, prosperous group of mainly Sephardim Jews who had immigrated to the city in the 1840’s from the Middle East. Resourceful and opportunistic, many had become enormously wealthy through successful ventures in textiles, silk, tea, opium, and real estate. Although small in number, the Sephardim Jews were woven prominently into the tapestry of Shanghai culture: the Sassoons, Hardoons, and Kadoories -- three of the richest families in Far East, built much of the face of the Bund, including the magnificent Cathay Hotel and the art-deco Marble Hall (Leichter).

There was also a second wave of Russian Jews escaping the Tsarist Pogroms. Among whom was J.J. Olmert, the grandfather of current Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Olmert, who settled in China's Northern city of Harbin after Russian Revolution. (Da)

In contrast with the first two phases, the Ashkenazi refugees from Germany and Austria fleeing Nazi persecution were downtrodden, penniless, and viewed Shanghai more as a temporary stop than a potential long-term residence. Because of its special political status as a city ruled jointly by the Chinese and an International Municipal Council, after Kristallnaught, Shanghai became the only port city where no visa was required for entry.

Bund in 1930s

Leaving the country became ever more urgent when the Gestapo started rounding up Jewish men for the concentration camps, releasing them only if they secured entry elsewhere. But Britain had closed the door to the Promised Land -- Palestine, and America, the land of promise, was equally tight-fisted. A host of other nations had impossible requirements. “New Zealand and Australia wanted sheep-herders,” Eva Hirschel said, “Do you know how many German Jewish sheep-herders there were? None.” (Hirschel). It was in these desperate conditions that so many Jews turned to Shanghai as their last resort, and it was in these conditions that one Chinese man made the great escape for many, possible.

Feng-shan Ho

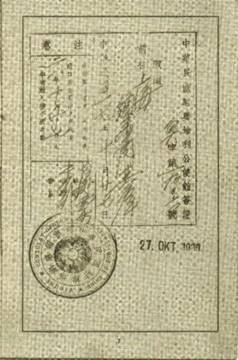

Dr. Feng-shan Ho was the Chinese Consul-General in Vienna in 1938, and for the

|

sixteen months following Kristallnaught, until China’s diplomatic break with the Nazis in 1940, he practiced a liberal visa policy, issuing the entrance documents to Shanghai to all who requested them in direct opposition of his government’s wishes. Ho was one of the first diplomats to employ such methods (Kremer). While a visa was not required to enter Shanghai, it was a safe pass necessary to leave Austria. |

In doing so, Dr. Ho saved over 2,000 lives, including Santa Rosa resident Hedy Durlester’s family, who escaped with his visas to the Philippines (Dregey 10).

In October 2000, two years after his passing in San Francisco, Feng-shan Ho was honored as a Righteous Among the Nations for his humanitarian courage. (Krashinsky, Burdman).

Dr. Ho had always been modest about his actions. He once said, “I thought it only natural to feel compassion and to want to help. From the standpoint of humanity, that is the way it should be” (Poy).

The Journey

But even with tickets and visas in hand, leaving the country in itself was a running gauntlet. Ursula Bacon remembers the painful and humiliating examinations she endured as her family took the train to Genoa, Italy in the spring of 1939: “Some woman did a spot check looking for people smuggling jewels out of the country. [Luckily], when she found nothing on us, she let us go” (Bacon 16).

Bacon, like thousands of other desperate refugees, would escape by way of German and Italian ships. Earlier on, there were fewer passengers, and the month-long voyage resembled more of a cruise. Later on, these ships soon became crowded hellholes, with poor food, poorer lodgings, and the ever present fear of persecution onboard.

Others took the train eastbound, through Poland and Siberia, heading south through Manchuria, which was under Japanese control. Either way, the journey was harrowing, and most Jews arrived in Shanghai with nothing but the allowed $5, a few smuggled valuables, and an indomitable will to survive.

The Life and Death in Shanghai

The stories that follow the Jewish refugee’s disembarkment on the Huangpoo are numerous and variegated. The city had been in the hands of the Japanese since November of 1937, but even so, Shanghai was still one of the most exciting places on earth. Fortunately for the penniless Jews, it was a place where “you could buy anything, trade anything, and make a living” (Bacon 23).

Those refugees who had money or connections found subleted rooms in the French Concession, or in cramped apartments on Huaihai and Fuzhou Road. Poorer Jews sought residence in the Hongkou district, where the wealthy Sephardim ran five refugee centers and seven synagogues that provided food and shelter. Yet conditions at the “homes” were atrocious. Hygiene was a perpetual problem. There were no toilets, no hot water, no lights, and no privacy. Human waste spilled out on the streets, and disease spread faster than the wind. But life went on in a way that would have only been possible in Shanghai.

Ingrid Gallin was three years old when her family left Berlin for “the Paris of the Orient”. They lived in Hongkou, “an old, poor shantytown area of Shanghai already overcrowded with Chinese civilians and Japanese soldiers”; her father sold shmatas or old clothes on the streets (Falbaum 47). Ingrid attended the Kadoorie Schule (School). Eventually, her father made enough money for them to move into a house on Broadway Street. But every day was a hard and bitter struggle. One particular memory has haunted her for years:

I remember witnessing a Chinese woman giving birth in a gutter, and a Japanese soldier bayoneted her and the newborn infant. At first, I hid because I was afraid the soldier had seen me. I went home and hysterically told of this horrible event which I recall to this day (Falbaum 47).

Shirley Temple and her friend Eva

Yet not all memories of Shanghai were bleak. Eva Hirschel, a resident of Rohnert Park, was 12 years old when she fled Germany in 1940. Like millions of other pre-teens around the world, she idolized Shirley Temple, and saw the child star as a reflection of herself – a German Jewish girl.

Eva wrote: “I had been in Shanghai only a few weeks when one day, walking down Wayside Road, I happened to pass a cinema and there to my utter joy and delight was a large poster from which Shirley’s eyes smiled at me. I could have hugged her. I was so happy and relieved.”

Eva ran home and told her mother about the news.

“Shirley. Shirley Temple. Isn’t that wonderful? She got out of Germany. She is safe and living right here in Shanghai. I know. I saw her picture” (LeBaron).

Eva left Shanghai as a nineteen-year old, having spent her teenage years in the city. Despite the hardship and the starvation, she thinks of her experiences as overwhelming positive: “We grew up so fast - we learned responsibility; we learned to help others, and each other. I don’t envy the kids here [in US] at all. I wouldn’t have traded it for the world.” (Hirschel)

Cultural Life

Trude Kutner arrived in Shanghai as a fifteen-year-old in 1938. Her family was housed in the private homes of white Russians, and her father received loans to open a joint business -- a Viennese eatery where she waited tables and her mother cooked as chef. In the evenings, Trude said, “There were bars and nightclubs with music, dancing, and entertainment…I often went straight from work to a dance and directly back to work at 6 am. No one was going to cheat me out of my opportunity to dance, not even Hitler” (Falbaum 140).

Thousands of other Jews survived much as Trude, Ingrid and Eva did -- with determination, resourcefulness, and a sort of relentless spirit that allowed them to prevail over the many challenges presented by a city where “God must have looked the other way when the devil moved in” (Bacon 22). A thriving, boisterous Jewish culture developed with first-rate theatre, ballet and concerts. Newspapers were printed in half-a-dozen languages, and intramural sports teams were organized. The Jewish quarter of Shanghai became known as “Little Vienna” (Gluckman).

Hongkou Ghetto

Up through the end of 1941, the Japanese occupiers of Shanghai, despite being allied with the Nazis, mostly let the Jews alone. The Japanese had never adopted the fascist ideology prevalent in Germany and Italy, nor did they harbor grudges against the Jews (Tokayer). Wealthy Sephardim had lent large sums of money to the Japanese in past years, and they repaid in kind by allowing the Jews to pass freely through the city.

|

All that changed with Pearl Harbor. Japanese policy towards

the Jews suddenly darkened. Those from Allied nations were sent to POW

camps. German and Austrian Jews, the largest group, were considered stateless

refugees, and were confined the Hongkou ghetto in 1943.

Leaving the ghetto required a pass, which could only be stamped by the fearsome Japanese commando, Ghoya. Because limited amounts of passes were handed out daily, working outside ghetto became a severe problem. No work meant no money, and even those who had cash didn’t fare much better. Eva Hirschel recalls that “[her] family lived in a house shared by 24 other people with one bathtub, cold water and two small toilets. [They] lived in one room, which was separated in half by a tiny plywood wall in order to accommodate another couple.” (Dregey 14, Martinez). Residents were told to boil everything, and if they couldn’t boil it, to soak it in potassium permanganate, which killed germs. Farmers often used human waste collected off the city streets as fertilizers, resulting in widespread dysentery and diarrhea. |

The Relationship with Chinese

In hardship and fear, the Jews and Chinese found a common theme that connected two ancient peoples together. The Chinese, too, suffered tremendously from WWII. Thirty five million civilians and soldiers were killed or wounded by the Japanese. Villages and cities across the country were reduced to ash and rubble. Yet in spite of their own plight, they showed immeasurable kindness and generosity towards the Jewish refugees.

Jerry Moses, a retired businessman from Los Angeles, remembered: “If we were thirsty, they [the Chinese] gave us water. If we were hungry, they gave us rice cakes. As bad as we had it, they had it worse. And they felt bad for us” (Minter).

In a recent diplomatic visit to China, Ehud Olmert, Prime Minister of Israel, stated, “We feel a lot of gratefulness for the Chinese people for the very warm and friendly manner in which they treated Jewish people both in Shanghai and in Harbin” (Xinhua).

Shanghai was hardly summer camp, but in the light of the fate of those who stayed behind, it might as well have been paradise. Nearly all of the Jews who had come to the city survived the war.

Knowledge

The Jews of Shanghai heard very soon of what had happened to their family and friends back in Europe. Listening to Eisenhower inspect the concentration camps, Eva Hirschel asked, “Who could have imagined? It was so quiet in our ghetto that you could have heard a pin drop. What could you say? There wasn’t a single person who hadn’t lost somebody. In 1940? Germany, this country of Goethe and Nietzsche and Brahms and Beethoven, that they would have concentration camps. I can never understand it” (Hirschel).

But when asked whether the Jews of Shanghai ever wanted vengeance, Eva shook her head furiously: “There was sadness. There was sorrow. There always will be sorrow. But revenge - no, no, never”

This statement will never cease to amaze me.

The End of the War

After the end of the war, most Jews looked towards new lives in the United States, Canada, Australia, and Israel. A few stayed behind to weather three more years of Chinese civil war, and the early days of Mao. But by the late 1950s, the once thriving Jewish ghetto had all but vanished. Today, there are few Chinese who are old enough to remember that Jews once lived among them.

The Historical Significance of the Event

The escape and survival of Jews in Shanghai is probably one of the least-acknowledged, least documented stories of Holocaust. Yet I believe that it should join the Danish resistance and the Anne Frank annex as one of the most courageous tales of bravery and the strength of human resilience. It also serves as a constant echo in people’s consciences. If more nations had opened their doors as Shanghai had -- how many more of the six million could have been saved?

The Shanghai Jews remain significant even sixty years after the Holocaust not only because of their sheer numbers, but because they have come to represent the Jewish people’s ability to adapt and endure, with spirit and song, much as they have done for three millennia. Eva recalled the can-do determination in which the Shanghai Jews faced their new lives: “Can you drive a truck? Of course we can. Can you do shorthand? Of course we can. We can do anything!” (Hirschel).

Shanghai, China, could not have been further from home, geographically and culturally. Yet ultimately, it was this leap of faith they took in stepping onto the Bund that allowed them to triumph over immense tragedy – and cheat Hitler out of 20,000 Jews.

Their lives today are as diverse as the hues in the muddy Huangpoo. But no matter where their paths lead, they will never forget that they were once a “Shanghailander”, and that it is to this city that they owe their gift of years. For Shanghai was indeed, “the lifeboat on the sea”.

Annotated Bibliography

Primary Sources

Bacon, Ursula. Shanghai Diary - A Young Girl’s Journey from Hitler's Hate to War-Torn China. Milwaukie: Milwaukie Press, 2002.

In her Memoir, Ursula Bacon recounts her childhood and struggles in Shanghai. It is written from a first person perspective, so is naturally biased and cannot be used to generalize, especially considering that Ursula had the unusual circumstance of connections with a warlord, and was better off than most.

Dregey, Miriam. An Event Honoring Holocaust Survivors and Supporters of Holocaust Education. Alliance for the Study of the Holocaust, September 7, 2006.

This is a collection of accounts of over 30 Holocaust survivors in Sonoma County, California.

Among them, three (Henry Fuhs, Eva Hirschel and Ruth Turner) lived in Shanghai for extensive periods of time and one (Hedy Durlester) escaped to the Philippines with Dr. Ho’s visa. It is valuable because of the personal accounts of the local survivors, and a certain degree of objectivity due to the range of the stories and experiences.

Falbaum, Berl. Shanghai Remembered…Stories of Jews Who Escaped To Shanghai from

Nazi Europe. Royal Oak: Momentum Books, 2005.

This book includes personal accounts of over 20 Shanghai Jews. I focused on the stories of two of them: Ingrid Gallin and Trude Kutner, whom I felt to embody many of the experiences, both positive and negative, of the Shanghai Jews. Because of the amount of stories and the variety of experiences, it can give a very good overall picture, enhanced by the feel of a sweeping narrative.

Hirschel, Eva. Personal interview in Rohnert Park, California. 22 March 2007.

It was an incredible experience for me to be able to talk to someone who had been a Shanghai Jew, and Eva’s honesty and willingness to tell her story was something to behold. I met Eva through an event at her synagogue, and our interview resembled more of a personal talk than an interview. She really didn’t need me to prompt her with questions, and ended up showing me many of her pictures from Shanghai. Especially poignant was her gratefulness towards the Chinese people, and a seeming lack of hatred towards the Germans. Just as I think the Holocaust brought out the worst in people, the Shanghai experience brought out the very best.

Kleinberg, Jody. “SR Woman finds long-lost Sister. Sleuthing Filled in holes in History.” The Press Democrat November 27, 1997.

This is a story of local Shanghai Jew Ruth Turner who learned recently that she has a half-sister in England. Her birth mother gave Ruth up for adoption in 1938 so that she could leave Germany quickly. She and her adoptive parents lived in Shanghai for about 10 years. In 1997, Turner finally traced down that her birth-mother escaped to England and had had another daughter (her half sister). The article helps to explain many of the desperate actions families were forced to take in order for any of them to escape the concentration camps.

Kremer, Roberta. “Diplomat Rescuers: the Story of Feng Shan Ho.” Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre, 1999.

The article contains valuable information on Dr. Ho, including intimate details as to how exactly he saved the Jews of Vienna. It includes survivor testimonies, scholars’ research, original documents, photos, and other information that was critical in constructing historically what happened. The article praises Dr. Ho, deservedly, but it is still not a truly objective source.

LeBaron, Gaye. “Shirley Temple and her friend Eva.” The Press Democrat April 5, 1995.

Gaye LeBaron, the staff writer of Press Democrat, wrote this article in 1995, including an essay by Eva Hirschel (a local Shanghai Jew) in which Eva described her childhood relationship with Shirley Temple. The story helped provide me with a polar contrast in the Shanghai experience. So much of it is bleak and dark that I felt it was important to also show that Shanghai was also where many memories were made.

Xinhua. “Olmert’s vist refreshes personal bond with China.” China Daily January 9, 2007.

This was an interview with Ehud Olmert, Prime Minister of Israel, before he left on an official visit to China at the beginning of 2007. He talked of his personal connections to China as well as his gratefulness to the Chinese people. Although well meaning, it was a blatant attempt at international public relations.

Secondary Sources

Burdman, Pamela. “OBITURARY – Feng Shan Ho.” The San Francisco Chronicle October 3, 1997.

This is the original text of Dr. Feng Shan Ho’s obituary. It described his lengthy career as a diplomat, and also mentioned his actions in Vienna, helping Jews escaping the concentration camps. The document put a more personal touch on the life and death of a man who affected so many lives and deaths.

Da, Shao. “Finding Family Roots at Harbin's Jewish Cemetery.” China.org.cn September 14, 2004.

This article, written in 2004, is about the Jewish people living in the city of Harbin of Northern China. Ehud Olmert was at the time the Israeli vice premier and trade minister. He visited his grandfather’s tomb in Harbin along with other Harbin Jews. China saved many Jews who would become extremely influential in global politics and business.

Falk, Gerhard. “The Jews of Shanghai.” Jbuff.com, 2003, <http://www.jbuff.com/c060304.htm>

This is the commentary by Dr. Gerhard Falk on the book The Jewish Refugee Community in Shanghai 1938-1945. Falk casts a rather critical and cynical light on the actions (or lack thereof) of western nations such as the US and Britain against the Holocaust. He describes the situation of the Evian Conference in 1938, when most European nations expressed contempt for German policy, but refused to take in Jewish refugees, thereby giving the Nazis leverage to continue on their course towards the Final Solution.

Gluckman, Ron. “The Ghosts of Shanghai.” AsiaWeek. June 1997.

Ron Cluckman is a San Francisco reporter who retraced his grandparent’s footsteps in Shanghai on a trip to China. The article was extremely helpful because it spanned the entire history of Shanghai Jewry, including the first and second waves of Jews. It also gives additional information about the present preservation of Jewish culture in China, and the gradual rebuilding of the Jewish community in Shanghai. Perhaps the most interesting portion was the list of famous Shanghai Jews – people like American pop artist Peter Max, former US secretary of the treasury Mike Blumenthal and Eric Halpern, founder of the Far Eastern Economic Review.

Krashinsky, Jonathan. “Chinese Official Named Righteous Among the Nations.” The Jerusalem Post 2000.

This is the official news report from The Jerusalem Post about Feng Shan Ho being honored as Righteous among the Nations. It was complimentary of his services, as expected of a report on an awards ceremony presented to a humanitarian and diplomat.

Leichter, Harry. Jews of Shanghai and their History Site. 21 Jan. 2007 <http://www.haruth.com/jw/China/AsiaJewsShanghai.htm>.

This is one of most comprehensive websites on the topic of Shanghai Jews. It contains many links to articles, testimonies, photos, etc. Although not completely objective, its articles carry a sort of flavor that renders the Shanghailanders more personable. I started my research from this site.

Martinez, Jaime. “Local survivors, who will be honored at Cotati event this weekend, share their stories.” The Community Voice September 15, 2006.

This is an article in the local newspaper about a gathering in Cotati to honor local Holocaust survivors. It turned out to be one of the best leads that I had. I attended the ceremony and met a number of local Shanghai Jews. From that, my research of this topic intensified.

Minter, Adam. “Return of a Shanghai Jew.” The Los Angeles Times January 15, 2006.

This lengthy article is about Shanghai Jew Jerry Moses of Los Angeles’ trip back to Shanghai. His account is interesting because it gives details about his interactions with local Chinese people, and his experience in returning to the city of his childhood.

Poy, Vivienne. “Tribute to Dr. Feng Shan Ho.” March 21, 2000.

This is a speech by Chinese-Canadian Senator Vivienne Poy (the first Canadian senator of Asian ancestry) in which she paid tribute to Dr. Feng Shan Ho. This is another typical awards prototype.

Robert, J.A. A Concise History of China. New York: Harvard University Press, 1996.

This compact and accessible book condenses 4000 years of Chinese history into 300 pages. It was used for background information about Shanghai in the 1930s. An objective source from a reliable publishing house, the book is a treasure trove of historical context and general China facts.

Tokayer, Marvin and Mary Swartz. The Fugu Plan: The Untold Story of The Japanese and The Jews During World War II. Jerusalem: Gefen Publishing House, 2004.

This book gives interesting insight as to why the Japanese did not follow Nazi demands to deport Jews back to Germany to be gassed in the concentration camps. The Japanese had read The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, recognizing that if they were to lose the war to America, they wanted to be on good terms with the “real bosses” of the US, i.e. the Jews. This twisted logic ironically saved the lives of the Jews who lived in Shanghai through World War II.